ThreeEssays in Cognitive Science

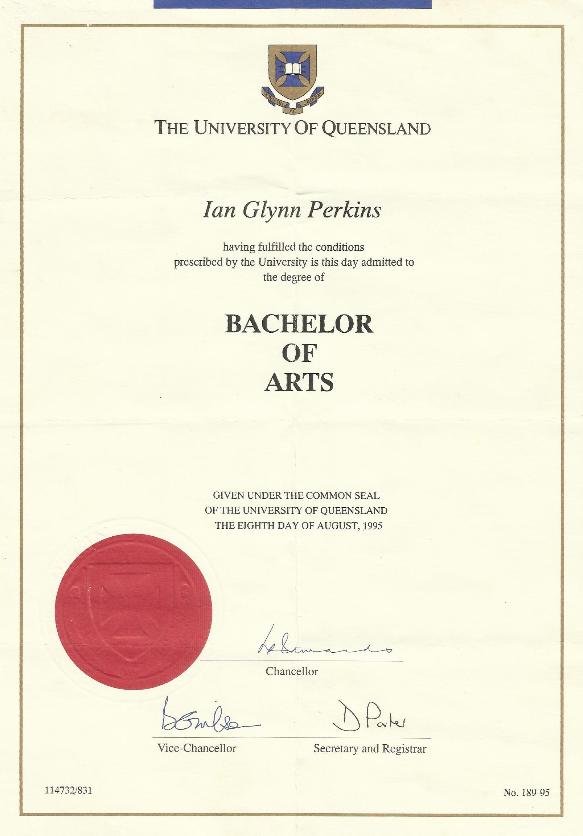

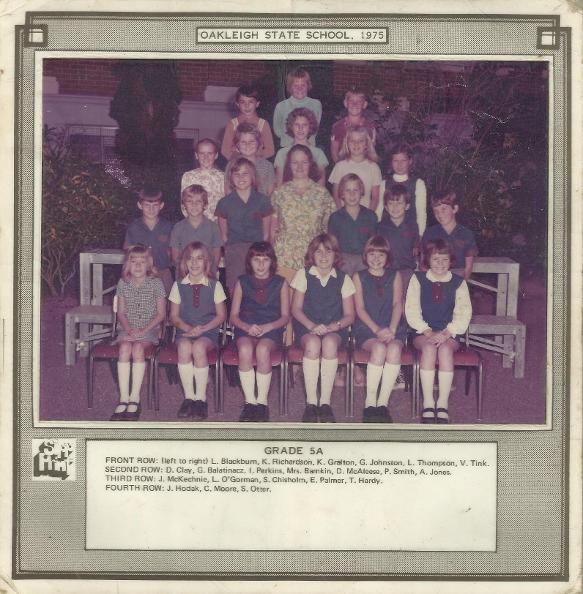

by Ian Glynn Perkins B.A.

(Linguistics & Cognitive Science, University of Queenland 1983-2002)

1.Nicotine:

Native America's Revenge:

Extinguishing Nicotine Dependency

Figure 1:

The Seal of the President of the USA, the country of origin of both Nicotiana and the major tobacco companies, misappropriated from indigenous cultural resources, is an eagle with a tobacco leaf held in the claw, symbolising American commerce.

A cigarette is the perfect type of a perfect pleasure. It is exquisite, and leaves one unsatisfied.

- Oscar Wilde

Nicotine, the principal alkaloid in tobacco, is a positively reinforcing, psychoactive euphoriant. Humans rapidly develop nicotine tolerance on repeated exposure, then display withdrawal on abstinence. Nicotine is rapidly active in the central and peripheral nervous systems after administration, and directly affects synaptic receptors, neurotransmitters and the endocrine system. Biomedical research has established nicotine's critical role in compulsive cigarette smoking behaviour.

Tobacco use is typical of compulsive drug dependency behaviour, and is usually established early in life, and consequently follows a typically developmental behaviour adoption pattern until complete psychophysiological dependence is achieved. The development of nicotine tolerance is central to the establishment and maintenance of tobacco use. Intermittent smoking can become compulsive within months of initiation, and early tobacco use is the major predictor of long-term smoking dependence. Mental illness also predicts tobacco use, but the converse is not necessarily true. Illicit drug use is similarly related.

Historically, capitalist tobacco interests have had unfettered access to markets & mind share, and have specifically targeted young people and other susceptible populations, deliberately reinforcing socially valued "secondary associations" with cigarette smoking in mass media imagery.

Tobacco smoking has complex operant and respondent conditioning relationships. For example, it can become a generalised, conditioned response to multimodal contextual stimuli conditioned to signal both availability and "proximate onset" of the pharmacological effects of nicotine. These cues may in turn become conditioned to nicotine itself and evoke nicotine-like or opposite organismic responses. Meta-analysis has demonstrated cue-reactivity effects across all classes of abused drugs, including tobacco.

The activity of tobacco smoking itself is a powerful unconditioned psychophysiological stimulus that associates with social outcomes, as nicotine is positively reinforcing in humans via common dopamine pathways. These positive social associations with the sensations and rituals of smoking, crucially reinforced by transient nicotine euphoria, maintain the behaviour: smoking is generally observed only as a mode of drug delivery, and inhaling smoke is otherwise generally considered aversive. All these associations are interactive, and may also interact with the stimulus-response cascades of other common psychoactive drugs of dependency. Control of negative affect, stress, and cravings associated with nicotine withdrawal, are also cited as important motivational factors in smoking maintenance and relapse. Thus, the everyday nature of tobacco smoking's contextual stimuli, its repetitive, immediate stimulus-response cascade, coupled with the psychoactivity of its alkaloids, represent a powerful model of psychophysiological substance dependence.

There is a large and varied literature of smoking treatments, but most quitting smokers either fail or relapse. Viswesvaran & Schmidt's (1992) meta-analysis of 633 smoking cessation studies across 15 treatment categories revealed an average baseline of only 18.6% of smokers remaining abstinent after 3 to 12 months, corrected for spontaneous cessation in control groups. Perhaps the key interpretation of these results is the indifferent success of any one type of smoking intervention.

Smoking abstinence following treatment is predicted by lower pre-treatment nicotine intake, therefore, progressively reducing nicotine intake or numbers of cigarettes smoked (fading) should improve maintenance of post-intervention abstinence, but empirical findings are mixed. Lando & McGovern (1985) recruited 130 subjects who smoked on average 30.1 cigarettes daily (M age = 37.9, smoking years = 19.7), randomly assigning them to four conditions: control, nicotine fading ("fading": switching to lower yield cigarettes on a weekly 20-25% nicotine yield reduction schedule), "fading" plus aversive "smokeholding", and aversive "oversmoking". The best initial results were for the combined aversive-"fading" condition. At 6 month follow-up, abstinence was worst for the "fading" group, and was undifferentiated from the controls. Subjects preferred "fading" over aversion, however. Farkas (1999), using telephone surveying, interviewed 1682 smokers about the level of their cigarette use and any fading behaviour, and followed them up after one to two years. "fading" did not significantly predict cessation in any category of smoker (heavy [25+ daily], moderate [15-25], or light) except for smokers who faded from heavy/moderate to light prior to abstinence. Although the self report methodology is weak, it appears heavy smokers who significantly fade before cessation are more likely to succeed than those who do not, or fade only moderately. Another, smaller (N = 7) study reported that 5 participants in a combination "fading, self-recording and contracting" treatment had maintained abstinence after two years (Singh & Leung 1988) but fading's contribution is unknown.

Nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) delivers nicotine withdrawal relief without the ritualised sensory contexts of cigarettes, and so is only minimally addictive. Cepeda-Benito's (1993) meta-analysis of 33 studies of gum-NRT in long-term smokers found all groups in NRT significantly more abstinent than controls at short term follow-up, but only groups receiving NRT combined with another therapy were significantly more abstinent at long term follow-up. Placebo effects having been excluded, it appears NRT has short term pharmacological benefit, but is only efficacious in the long term as an adjunct to other therapies, though methodological variability limits the reliability of this conclusion. Similarly, Fortmann and Killen (1995), using a random sample of 1044 smokers assigned to gum-NRT, self-help materials, NRT plus self-help, or counseling conditions, found significantly more abstinence in the NRT conditions at six month follow up.

Immediate control of drug cravings has been demonstrated using nitrous oxide (N2O), a safe, legal, short-acting gaseous analgesic and euphoriant (Daynes & Gillman 1994). Of 480 South African Caucasian, Zulu and Asian patients in treatment for alcohol, cannabis or tobacco dependence presenting with cravings, 84% reported craving abolishment, and 14% reduction, after 20 minutes inhalation of oxygen and N2O for 20 minutes using dental analgesia equipment. No follow-up was conducted. Lewin, Biglan & Inman (1986) investigated whether muscle tension in three randomly selected smokers could be operant-conditioned to smoking, thereby contributing to withdrawal and relapse. Subjects' baseline EMG was recorded, and, in the response-contingent trials, were signaled by a tone to puff on a cigarette whenever pre-set EMG criteria were recorded. Probe trials of the contingent tone were also conducted. They found a significant increase in EMG activity in most response-contingent trials, and higher than baseline EMG in probe trials. They concluded that tension was reinforcable by smoking, and may play a role in the relapse crisis. Therefore, relief of muscle tension may be a useful adjunct to other smoking cessation treatments.

Contingency contracts are somewhat effective in inducing smoking abstinence. Spring, Sipich, Trimble & Goeckner (1978) assigned 42 smokers to three conditions: signing a contingency contract to quit smoking punishable by fine; signing a non-contingency contract, and control. 71% of subjects in the contingency contract condition were abstinent at post-treatment, significantly greater than non-contract (14%) and control (23%). However, significant differences had disappeared at one year follow-up, and in all groups, fewer than one quarter of subjects had remained abstinent. In contrast, Singh & Leung (1988) found most subjects had maintained abstinence after two years in a "fading, self-recording and contracting" treatment combination, but the contract's individual contribution to this success is unclear.

Successful treatment of smoking may depend on concurrently treating the nicotine withdrawal syndrome, cognitive-operant smoking motivations, and stress, a major precipitant of smoking relapse. Combinations of interventions also appear to be more efficacious. The main contingencies that maintain smoking are: negative reinforcement by relief of cravings and negative cognitions; and, positive reinforcement by successful socialising, satisfying oral and manual sensory and kinesthetic behaviour patterns, and euphoria.

As combined treatments seem more effective, successful treatment of smoking behaviour is likely to depend on an integrated intervention that (1) permits extinction or satisfaction of nicotine cravings, a major cause of smoking relapse, without recourse to smoking; and, (2) motivates the smoker sufficiently to consciously overcome their complex smoking cue reactivity. Stress and negative affect, other major precipitants of relapse should also be addressed. Therefore, a combination of contingency-contractual fading, NRT, extreme craving control with N2O, and relief of psychomotor tension through relaxation and exercise is probably likely to extinguish a motivated quitter's smoking behaviour permanently.

Smokers who have failed to extinguish smoking by simple reduction and abstinence due to cravings and stress cannot be expected to maintain abstinence without craving and stress management. Given a history of substance use, modality or substance substitution should be a well established responding circuit, therefore, NRT, in the form of inhaler is appropriate to relieve the pharmacological, and manual and oral behavioural aspects of smoking cravings. Coupled with the rapid delivery of nicotine, this should both provide craving relief and protect against incidental relapse. NRT should begin during the last week of cigarette fading, or immediately upon abstinence. The NRT itself will be faded on a schedule deemed appropriate on treatment progress. However, it is likely that, at times, and in reactive contexts, that the smoker's subjective experience of cravings may become unmanageable, even during NRT, and lead to incidental relapse, thereby providing some variable ratio reinforcement of smoking and therefore resiliency to extinction. In such situations, it is advised to inhale 10 cm3 of N2O every 5 minutes until cravings have been abolished. N2O is a non-addictive opioid agonist and is a recognised withdrawal therapy in some jurisdictions (Daynes & Gillman 1994).

Stress, anxiety and depression are major immediate stimuli for smoking behaviour, therefore some form of affect management is required, as complete avoidance of negative affect triggers may be impossible. Unlike cravings, the smoker's negative affect states are not originally caused by their smoking behaviour, although both nicotine euphoria and the subsequent withdrawal syndrome may be a discriminative stimulus of stressful or anxious situations for them. Since muscle tension can be conditioned to smoking, feelings of tension may also be a discriminative stimulus, signally the onset of nicotine reward, thereby maintaining smoking ("I am tense, I will therefore smoke"), beginning a cascade of negative reinforcement (stress relief). Therefore, ex-smokers are encouraged to begin and maintain a regular, daily schedule of structured exercise and relaxation, each a minimum of 30 minutes in duration. Any structured, continuous exercise program may be employed, from brisk walking, cycling, to gym workouts. The more intense the exercise the better. This will have the additional benefits of: modeling a healthy lifestyle; providing additional motivation (health & fitness); stimulating the ex-smoker's endogenous opioid reward system without drugs; and providing some sense of self-efficacy. In conjunction, ex-smokers should also take time to relax, at least once daily in a gentle exercise program such as Tai Chi, or meditating. They are encouraged to either exercise or meditate, if practical, in response to cravings before recourse to N2O.

This intervention is based on a limited review of a vast literature whose principal finding is that smoking cessation is unlikely to occur for most nicotine-dependent subjects, and that abstinence rates at long term follow-up are low (Scheider 1984).

Select Bibliography

Carter, B. & S. Tiffany (1999). Meta-analysis of cue-reactivity in addiction research. Addiction, 94 (3), 349-351.

Cepeda-Benito, A. (1993). Meta-analytical review of the efficacy of nicotine chewing gum in smoking treatment programs. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology, 61 950, 882-830.

Daynes, G. & M. Gillman (1994). Psychotropic analgesic nitrous oxide prevents craving after withdrawal for alcohol, cannabis and tobacco. International Journal of Neuroscience, 76, 13-16.

Fiorer, M., P. Newcombe & P. McBride (1993). Natural history and epidemiology of tobacco use and addiction. In: Orleans, C.T. & J. Slade (Eds.). Nicotine Addiction. (pp. 89-104). New York: Oxford University Press.

Fisher, E., E. Lichtenstein & D. Haire-Joshu (1993). Multiple determinants of tobacco use and cessation. In: Orleans, C.T. & J. Slade (Eds.). Nicotine Addiction. (pp. 59-88). New York: Oxford University Press.

Flay, B. (1993) Youth tobacco use: risks, patterns, and control. In: Orleans, C.T. & J. Slade (Eds.). Nicotine Addiction. (pp. 365-384). New York: Oxford University Press.

Fortmann, S. & J. Killen (1995). Nicotine gum and self-help behavioural treatment for smoking relapse prevention: results from a trial using population based recruitment. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology, 63 (3), 460-468.

Henningfield, J., C. Cohen & W. Pickworth (1993). Psychopharmacology of Nicotine. In: Orleans, C.T. & J. Slade (Eds.). Nicotine Addiction. (pp. 24-45). New York: Oxford University Press.

Hurt, r., K. Eberman, J. Slade & L. Karan (1993). Treating nicotine addiction in patients with other addictive disorders. In: Orleans, C.T. & J. Slade (Eds.). Nicotine Addiction. (pp. 310-326). New York: Oxford University Press.

Jones, R. (1992). What have we learned from nicotine, cocaine and marijuana about addiction? In: O'Brien, C. & J. Jaffe (Eds.). Addictive States. (pp. 109-122). New York: Raven Press.

Kornetsky, C. & L. Porrino (1992). Brain mechanisms of drug-induced reinforcement. In: O'Brien, C. & J. Jaffe (Eds.). Addictive States. (pp. 59-77). New York: Raven Press.

Lando, H. (1977) Successful treatment of Smokers with a broad-spectrum behavioural approach. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology, 45 (3), 361-366.

Lando, H. & P. McGovern (1985). Nicotine fading as a nonaversive alternative in a broad spectrum treatment for eliminating smoking. Addictive Behaviours, 10, 153-161.

Lewis, L., A. Biglan & D. Inman (1986). Operant conditioning of EMG activity using cigarette puffs as a reinforcer. Addictive Behaviours, 11, 197-200.

Lichtenstein, E. (1971). How to quit smoking. Psychology Today, 4 (8), 42-45.

Lipp, O. (2002). The self-monitoring project. [on line]. Accessible from: http://www2.psy.uq.edu.au/coursematerial/py293/PY269/sorck/index.html

O'Brien, C., A. Childress, A.T. McLellan & R. Ehrman (1992). A learning model of addiction. In: O'Brien, C. & J. Jaffe (Eds.). Addictive States. (pp. 157-177). New York: Raven Press.

Peters, M. & L. Morgan (2002). The pharmocotherapy of smoking cessation. Medical Journal of Australia, 146, 486-490.

Schneider, S. (1984). Who quits smoking in a behavioural treatment program? Addictive Behaviours, 9, 373-381.

Singh, N. & J.-P. Leung (1988). Smoking cessation through cigarette-fading, self-recording, and contracting: treatment, maintenance, and long-term follow-up. Addictive Behaviours, 13 (1), 101-105.

Slade, J. (1993). Nicotine delivery devices. In: Orleans, C.T. & J. Slade (Eds.). Nicotine Addiction. (pp. 3-23). New York: Oxford University Press.

Spring, F., J. Sipich, R. Trimble & D. Goeckner (1978) Effects of contingency and noncontingency contracts in the context of a self-control-oriented smoking modification program. Behaviour Therapy 9 (5), 967-968.

ALL CONTENT Copyright 1965-2014

by HRUs of Flyte 93

for Ian Glynn Perkins

all rights reserved.

2. Biological correlates of homosexuality.

(see below)

3. Magick & Psychology

CONTENTS

0. Personal experience

1. Cognitive illusions of causality & the sheep-goat effect

2. Belief-induced response bias

3. Illusions of control

4. Repetition avoidance bias in subjective random generation tasks

5. Ideologically driven experimenter bias confounds operalisation of belief in ESP?

6. The null hypothesis

7. Experimental method

8. Results and statistical analysis

9. Is psychology a crock of shit?

10. Biased constructs and instrumental artifacts?

11. References

12. Appendix: raw data

(for the full discussion, data, analysis and

references, see below )

_____________________

2.Biological correlates of homosexuality.

According to Breedlove (1994), the nature-nurture debate is a "facile dichotomy" between competing discourses of measurement technique within psychology. Psychological stimuli can produce biological changes, just as biological stimuli can produce psychological changes in organisms. In the absence of rigorous experimental data, the direction of the relationship between biology and behaviour cannot be inferred (Breedlove 1994).

This essay briefly examines some biological correlates of homosexuality, including genetic, neurological and hormonal data. It argues that the causal factors in human sexuality are yet to be determined, that homosexuality is multivariate construct, and that operationalisation of homosexuality is subject to bias.

Twin concordance studies have suggested that at least some of the incidence of homosexuality can be attributed to genetics (Burr 1993, LeVay & Hamer 1994). Combined data from six studies comparing monozygotic and fraternal twins and their siblings, where one twin is homosexual, indicate a 57% concordance rate for homosexuality in male identical twins, whereas concordance for male dizygotic twins was 24%, and 13% for siblings, compared to a 2% baseline. Results for women were slightly weaker but similar (LeVay & Hamer 1994).

About half the variance of sexual orientation in these results is attributable to genetic factors. It also implies, however, that some incidence of homosexuality is not attributable to genetic factors alone (Breedlove 1994), and therefore, like intelligence, homosexuality is a multifactorial trait (Burr 1993).

A linkage study examining the genomes of gay brothers suggested the presence of a gene on the X chromosome that possibly influences the sexual orientation of males (LeVay & Hamer 1994), but as not all gay brothers in the study had this genetic linkage, again, there must be other factors influencing male homosexuality (Breedlove 1994).

Studies of the brains of homosexuals have been based on the premise that they are feminised, by analogy with the sexual dimorphism found in mammalian brains, including, to some extent, humans (Breedlove 1994).

Some few studies have reported differences in brain structure between homosexual and heterosexual men, particularly in the anterior commissure, and regions of the hypothalamus, which appear feminised in homosexuals (LeVay 1996).

The first discovery of dimorphism between gay and straight men was in the suprachiasmatic nucleus of the anterior hypothalamus, which was not, however, dimorphic between the sexes, (Breedlove 1994).

In his classic study, LeVay hypothesised, on the basis of rat models, that specific hypothalamic nuclei would be correlated with sexual attraction to females, and would display dimorphism in human brains according to sexual orientation, and this was confirmed for men (LeVay 1996).

Byne (1994) has criticised LeVay's work on several fronts, however, pointing out that all the homosexuals studied had died of AIDS, a possible confound, although LeVay did attempt to control for this (LeVay 1996). Furthermore, his results have not been replicated, nor did they correspond well to earlier brain sex dimorphism studies (Byne 1994). Furthermore, sexually dimorphic brain structures have not been shown to be congenital in humans, therefore the direction of the relationship between sexuality and neurology is unclear (Breedlove 1994).

Animal experiments show that manipulation of fetal sex steroidal exposure affects the typicality of adult sexual behaviour (LeVay 1996) and brain morphology (Breedlove 1994). Specifically, critical timing of fetal exposure to androgens masculinises the brain of the animal by a complex hormonal process regardless of chromosomal sex. Inhibiting androgens causes feminisation to occur (Breedlove 1994). Masculinised females display male-typical mounting behaviour, rather than female-typical lordosis, and a (presumed) sexual preference for females. Feminised males do the opposite. These results have been found in several species, including primates (LeVay 1996, Breedlove 1994).

It has been hypothesised from this model that human sexual orientation may be organised by in utero levels of androgens, again on the premise that male homosexuals are feminised.

Consistent with this theory is data from persons with congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH) and androgen insensitivity (AI).

In CAH chromosomal females, excess androgen production causes some external masculinisation of the genitals, but they are typically identified as females at birth, and surgically altered accordingly. As children, these women are more likely to display sex atypical play behaviour, and are lesbians as adults more frequently than control populations (Breedlove 1994), but the relationship is weak and cannot be the sole factor in homosexuality (LeVay 1996).

In AI, chromosomal males are unaffected by androgens in utero and develop a female phenotype. They are considered female at birth and as adults display female typical gender identity and sexual behaviour (Breedlove 1994).

However, it would appear that the mechanisms for masculinising the brain remain intact in persons with AI, and masculinisation of the brain should have occurred (Breedlove 1994). Thus orientation of may of AI individuals may be the result of social learning, as they are socialised as females from birth (LeVay 1996).

All the biological variables discussed are correlated with the incidence of homosexuality, but in each case, only some of the variance is explained (genetic and hormonal correlates) or the direction of the relationship is obscure (neurological and hormonal correlates) (Breedlove 1994, Byne 1994). Homosexuality is clearly multivariate.

In the case of brain structure, it is not clear that the animal model is particularly valid in humans for sex difference of the brain (Breedlove 1994, Byne 1994, LeVay 1996), and extrapolations from sexual dimorphism to orientation dimorphism are based on the assumption that homosexuality is sex-atypical. There are doubts about the validity of this operationalisation, as homosexuality includes a variety of behaviours that are not easily classifiable with such a binary scheme (LeVay 1993).

The ideological implications of constructions of homosexuality for institutional abuse are well attested and have persisted in psychology beyond the Nazi period into the fifties. Homosexuality was still a psychiatric pathology as late as 1973. (LeVay 1996) Issues of experimenter bias are therefore crucial in any operationalisation of homosexuality. To his credit, LeVay openly admits his gay activist political agenda in hypothesising that homosexuality is biologically based (LeVay 1996), and maintains standards of good science. We can only hope psychological research on this topic continues with the same openness.

References cited.

Burr, C. (1993). Homosexuality and biology. The Atlantic Monthly, March. 47-65.

Byne, W. (1994). The biological evidence challenged. Scientific American, May. 50-55.

Breedlove, S.M. (1994). Sexual differentiation of the human nervous system. Annual Review of Psychology, 45. 389-418..

LeVay, S. (1993) The Sexual Brain. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

LeVay, S. (1996) Queer science: The Use and Abuse of Reseach into Homosexuality. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

LeVay, S. & D. Hamer (1994). Evidence for a biological influnence in male homosexuality. Scientific American, May. 44-49.

______________________

3.

MAGICK & PSCHOLOGY:

Do "belief in the paranormal" constructs predict repetition avoidance in subjective random generation tasks?

OR:

Is post-industrial capitalist psychology adequate to investigate the widely attested phenomena the wise still call Magick?

0. Personal experience

"Personal experience" is often cited as the basis for people's belief in extra-sensory perception (ESP) (Blackmore 1992, Blackmore &Troscianko 1985).

1. Cognitive illusions of causality & the sheep-goat effect

Blackmore (1992), seeking reasons for these beliefs, theorised that some such experiences are attributable to "cognitive illusions of causality", epiphenomena of cognitive processing, analogous to visual illusions. If effects of such illusions can be demonstrated, they may explain, without recourse to positing ESP, the "sheep-goat effect" (SGE), the robust tendency of believers in paranormal phenomena ("sheep") to score higher on ESP tasks than non-believers ("goats") (Brugger, Landis & Regard 1990).

2. Belief-induced response bias

Since ESP research target sequences have been consistently shown to be biased against true randomness, including a lack of repetitions, the SGE may be an artifact of belief-induced response bias statistically matching a biased target series (Brugger, Landis & Regard 1990).

Subjective estimations of randomness are typically inaccurate (Blackmore &Troscianko 1985, Blackmore 1992), and ESP believers and non-believers might possibly be differentiated by their degree of perceptual shift, with believers predicted to perform worse than non-believers (Brugger et. al. 1990).

3. Illusions of control

Similarly, Langer and Roth (1975) predicted that skill-attribution in an apparently random task would be greater for both "actors" (participants making the predictions) than "observers", and when correct predictions were reinforced at the beginning of a trial (the actual sequence of success at prediction was predetermined). Skill-attribution was significantly more likely in both conditions, demonstrating an "illusion of control" (Blackmore 1992) and positive self-attribution.

Specific investigations into the relationship between the "sheep-goat effect" (SGE) and subjective random generation (SRG) have had mixed results, however.

4. Repetition avoidance bias in subjective random generation tasks

Blackmore and Troscianko (1985) found some evidence that believers performed worse on subjective probability tasks, but few of their results were significant. Specifically, there was no significant difference between believers and non-believers in numbers of consecutive doubles produced in a five digit SRG task, and an overall repetition avoidance bias (RAB).

Bruggeret. al. (1990) studied repetition avoidance as a "function of belief in ESP", but based on a simple operationalisation of ESP belief, found nothing significant in a "telepathy" experiment, and an overall repetition avoidance bias or RAB.

In a paced subjective random generation or SRG experiment however (experiment 2), believers had a significantly greater RAB, and in a further experiment, made significantly more incorrect guesses of probability, again based on a simple operationalisation of belief (Brugger et. al 1990).

5. Ideologically driven experimenter bias confounds operalisation of belief in ESP?

However, this operationalisation of belief in ESP seems inadequate, and perhaps a general ideologically driven experimenter bias is revealed by the puritan-like apocalyptic gospel allusion conventionally used as labels of the independent variable (IV):

“When the Son of man shall come in his glory, and all the holy angels with him, then shall he sit upon the throne of his glory. And before him shall be gathered all nations: and he shall separate them one from another, as a shepherd divideth his sheep from the goats.” The Bible: Matthew 25:3: [emphasis added]

6. The null hypothesis

Therefore, employing a more sophisticated operationalisation, the Belief in the Paranormal Scale (BPS) (Jones, Russell &Nickle 1977), and replicating Bruggeret. al.'s (1990) second subjective random generation or SRG experiment, it is hypothesised that belief in the paranormal does not predict repetition avoidance bias (RAB) in SRG tasks, and that repetition avoidance bias is a general effect in subjective random generation tasks.

7. Experimental method

Participants. A sample of first year psychology students (N=366) was recruited.

Materials used in the experiment were: a response sheet (for subjective random generation of imagined die rolls; a pencil; a ruler; and, the Belief in the Paranormal Scale questionnaire (BPSQ; see appendix).

Design and Procedure.A quasi-experimental, independent groups design was used. Participants were allocated to groups of three, and assigned one of three roles: the experimenter, the participant and the scribe. The experimenter instructed the participant to imagine a die rolling with their eyes closed, and to report the die rolls in time to the experimenter's tapping of the ruler at approximately 1 second intervals. The scribe recorded the participants die rolls on the response sheet and instructed the participant to stop after 66 responses. Subjects then swapped roles and repeat the procedure, until every subject has participated in each of the three roles. Subjects then completed the BPSQ. The independent variable was operationalised at two levels by selecting the scores below the 10th and above the 90th percentile of the BPSQ score distribution (non-believers and believers, respectively). The dependent variable or DV was operationalised as number of digit repetitions per 66 die responses.

8. Results and statistical analysis

Overall, the mean number of repetitions was much lower than expected by chance (3.74>10.8) and lower than reported by Brugger et. al. (1990). The IV was approximately normally distributed. The DV was highly positively skewed with high positive kurtosis. The elimination of five outliers shifted this distribution towards more normality [emphasis added] (see Appendix for raw data). Mean score on the Belief in Paranormal Scale Questionnaire or BPSQ was 70.22, with a standard deviation of 16.18, in a range from 32 to 116. Mean number of subjective random generation (SRG) repetitions was 3.74, with a standard deviation of 3.38, in a range from 0 to 14.

In order to strongly operationalise the BPSQ variable at two distinct levels, the top and bottom ten percentiles of the frequency distribution of raw Belief in Paranormal Scale Questionnaire scores were defined as believers and unbelievers, respectively (see Appendix for the raw data). The mean number of SRG repetitions for believers was 3.89, standard deviation: 2.65; for unbelievers; 4.39, standard deviation: 3.7.; overall 3.74, standard deviation 3.38.

An independent groups t-test was applied to the difference in mean SRG repetition scores of the two groups but the result was highly insignificant (t[70]=0.66, p>.05), as this data set is a highly probable snapshot of the null hypothesis (p=.51). Less than one percent of the variability in the DV is attributed to the IV (eta squared=0.006; see Appendix E).

9. Is psychology a crock of shit?

As predicted, the null hypothesis was supported. The operationalisation of the IV may have had an effect in this study as compared to Bruggeret. al.'s (1990) construct of belief, and could account for the present contradiction of their results. Certainly, this result offers little support to the artifactual origin of the "sheep-goat effect" (SGE) theory, as almost none of the variability in subjective random generation (SRG) repetition avoidance bias (RAB) was attributed to Belief In Paranormal Scale Questionnaire (BPSQ) score.

Overall, the strong mental misrepresentation of probabilities indicated by the high degree of repetition avoidance in this sample may be an important issue in the psychology of gambling addiction, and other high-risk behaviour syndromes.

10. Biased constructs and instrumental artifacts?

There are clear implications for the validity so-called sheep-goat effect (SGE) in ESP research: operationalisation of construct variables are seemingly fraught with the possibility of bias, and perhaps, rather than the sheep-goat effect (SGE) being a cognitive artifact, it may be an artifact of the survey instrument's design.

Obviously, the validity of the IV construct is questionable. Although the BPSQ represents an advance in measuring "paranormal" belief over earlier efforts in "sheep-goat effect" (SGE) research, it is also subject to serious criticism, as, e.g. no questions concerning conventional religious belief in miracles, for example, are posed, systematically excluding organised (i.e legitimate, socially normative religious) belief in paranormal phenomena.

At the present stage of research, operationalisation of the "belief" construct variable is a crucial issue. It may be that as the construct of belief is refined into a genuine psychological variable, the "sheep-goat effect" (SGE) will virtually disappear, but this question is an object for further research.

11. References

Blackmore, S. (1992) Psychic experiences: psychic illusions Skeptical Inquirer 16 pps. 367-376

Blackmore, S. & T. Troscianko (1985) Belief in the paranormal: probability judgements, illusory contro, and the 'chance baseline shift'. British Journal of Psychology 76. Pps. 459-468

Brugger, P., T. Landis & M. Regard (1990) A 'sheep-goat effect' in repition avoidance: extra-sensory perception as an effect of subjective probability? British Journal of Psychology 81. Pps. 455-468

Jones, W., D. Russel& T. Nickel (1977) Belief in the Paranormal Scale: an instrument to measure beliefs in magical phenomena and causes. JSAS Catalogue of Selected Documents in Psychology 7:100 (Ms no. 1577).

Langer, E. & J. Roth (1975) Heads I win, tail's it's chance: the illusion of control as a function of the sequence of outcomes in a purely chance task. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 32 (6) Pps. 951-955

12. Appendix: raw data

IV: BPSQ scores (ranked, ascending):

32 32 33 3333 34 34 36 36 37 38 3838 40 40 41 414141 42 42 43 4343 44 444444 45 4545 46 47 4747 48 48 49 49494949 50 50505050505050 51 5151 52 5252 53 535353535353535353 54 55 55555555 56 57 575757575757575757 58 585858585858 59 595959 60 606060606060 61 6161616161 62 6262626262626262 63 636363636363 64 64646464 65 6565656565 66 66666666666666 67 676767676767 68 6868686868 69 696969696969 70 70707070707070 71 717171717171717171 72 7272727272 73 73737373737373737373737373 74 74747474747474 75 7575757575 76 767676767676767676767676 77 7777777777777777777777 78 787878 79 797979797979797979 80 8080808080808080 81 818181818181818181818181 8181 81 82 828282828282828282 83 8383838383 84 8484848484 85 85858585 86 868686 87 878787 88 888888 89 8989898989 90 90909090 91 9191919191 92 93 939393939393 94 95 959595 96 969696 97 979797 98 989898 99 100 100 103 104 110 116

DV: Number of SRG Repetitions (paired with IV above):

5 6 2 3 9 0 6 3 8 6 4 14 26 2 3 0 0 2 5 0 4 0 1 3 0 3 7 8 0 3 10 11 1 3 7 9 10 2 22 3 5 0 000 3 4 44 1 2 6 1 2 2 0 0 1 2 3 4 5 8 13 14 2 22 4 6 9 9 0 1 2 2 3 4 4 8 8 9 0 0 1 4 6 66 1 2 4 6 0 0 2 4 9 9 11 0 1 4 5 7 12 0 00 1 1 3 4 10 11 0 00 2 22 5 0 0 1 1 4 0 2 4 7 9 11 1 1 2 3 4 9 11 13 0 0 1 2 3 6 7 0 1 2 3 4 10 0 00 3 5 6 11 0 1 1 3 33 4 7 0 00 2 3 5 5 8 8 13 0 1 5 7 9 12 0 0 1 1 2 3 4 4 5 55 9 9 13 0 000 1 1 2 16 0 0 1 5 7 12 0 1 11 2 3 33 4 5 5 6 13 0 00 1 1 2 5 6 7 77 8 1 2 5 9 1 1 2 2 3 5 6 7 8 13 0 0 1 2 2 3 33 6 0 000 1 1 4 5 555 7 8 88 19 0 00 1 1 2 22 5 5 0 2 5 6 7 8 1 1 3 4 5 25 0 3 4 4 12 0 1 1 5 3 3 4 5 0 2 9 10 0 3 4 5 5 7 0 2 3 8 9 1 3 3 4 5 6 8 2 2 4 4 6 7 8 4 0 3 3 9 0 3 6 7 0 3 4 8 0 0 1 3 0 3 8 3 20 4 6

Believers and unbelievers (the top and bottom ten percentiles of the BPSQ score distribution [IV]) SRG repetition scores [DV]:

Believers: 3 3 4 5 6 8 2 2 4 4 6 7 8 4 0 3 3 9 0 3 6 7 0 3 4 8 0 0 1 3 0 3 8 3 4 6

Unbelievers: 5 6 2 3 9 0 6 3 8 6 4 14 2 3 0 0 2 5 0 4 0 1 3 0 3 7 8 0 3 10 11 1 3 7 9 10